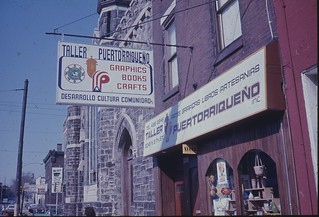

Latino communities transform public places in their communities into personal ones. These transformations fit with the idea of making a home, for a specific place is more than a house or address; it is the space plus the emotional and intellectual connections that become associated with that address and structure over time. In the book Diálogos, Placemaking in Latino Communities, the writers discuss one definition of place as referring to âterritorialized local communities, collective memories associated with territory, claims of authenticity by local actors, phenomenological associations with locales, and social relationships among people in territorial communities.â[1] In other words, place connotes a communityâs shared history and experience. The Latino communities of Philadelphia prove this with the music blaring from windows, the murals they choose to put on the sides of their buildings, and the colors with which they embellish their shops. It is, too, in the names they use to name their areas (el Barrio, el Centro de Oro) and in the names of institutions and businesses that string neighborhoods together (HACE, Centro Musical, Roberto Clemente High School, Congreso de Latinos Unidos, Taller Puertorriqueño). It is also marked in the colors and patterns of their national symbols that adorn their busineses, like the white cross with the alternating red & blue of the Dominican Republicâs flag, in the bands of green, white and red of the Mexican flag or in the sky blue, white and red stripes of the Puerto Rican flag. Each is read as a multifaceted proclamation of identity, of coming from one region, of having staked a claim in this area, in this space and for this time.

Taller Puertorriqueño (Taller) recognizes its connection to the community. It knows that through its work it has questioned the misnomer of “Badlands” to the area it is in, and reclaiming the pride of culture and contributions of Latinos in this community. With its Meet the Author Series[2], its Annual Arturo Schomburg Symposium[3] and collaborations with universities and colleges, Taller crosses boundaries, challenges stereotypes and inspires the civic engagement. In its youth education programs it fosters knowledge of arts, cultural history and critical thinking; its 20 years of association with the Philadelphia Art Museum is a great indicator of being a leader in using art as a bridge to cultural and community understanding. It knows it has played a role as an anchor of the neighborhoodâs identity, and as a resource and gateway to and for the Latino community. Students and patrons, both from around the city and within the neighborhood, come to Taller to learn about the cityâs Puerto Rican roots and its ever-increasing Latino diversity. More importantly within its programs, it offers context and a safe place to discuss and face very delicate and volatile issues such as gentrification and the long history of prejudice and classism towards Latino’s in this country. To better understand Tallerâs place and its place-making role in the Latino community of Philadelphia, we must look to its

origin.

|

| Raising the Puerto Rican flag in Taller  Puertorriqueño |

Taller was founded in 1974 in the basement of Aspira, Inc.[4], with a focus on bringing to the forefront, through practice, the arts and culture of the Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia. In the beginning, it ran a silk-screening operation where its members learned printmaking skills and a âpractical understanding of their history.â[5]Â This was during a time of tremendous upheavals and activism coming after the 60âs when, as Lorrin Thomas writes when talking about the Puerto Rican experience in NY, âWith deindustrialization as a stark backdrop of the communityâs struggles in the sixties, along with new debates about its âculture of povertyâ and then the radicalization of the African American civil rights movements, politicized young Puerto Ricans began to challenge the moderate, liberal approach of the older second generation and embrace a more radical agenda that would shift the balance of Puerto Rican activism in New York by 1970.â[6]

|

| Silk screening in Taller. |

As in New York, the same activism in Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia âemphasized the demands for recognition as a group alongside more standard claims for individual rights.â[7] This was Philadelphia in the heyday of the Young Lords, who on some of their posters demanded âHealth, Food, Housing and Educationâ in reaction to the massive under- and unemployment, deteriorating public services and lack of housing.[8] This was at the time of âthe increasing militancy of young radicals who were animated by the Cuban revolution, by decolonization struggles across Africa and Southeast Asia, and by their opposition to the United Statesâ war in Vietnam.â[9] Social justice, better housing, jobs and even the independence of Puerto Rico were the mantras of many at that time. So, when Domingo Negrón, Rosemary Cubas, Mike Fucille, Mario Rivera, Ramonita Rivera and Rafaela Colón founded Taller as a collective, it was under these goals and ideals. Israel Colón describes institutions like Taller as having âpursued a fine line between cultural affirmation and resistance.â[10]

In Tallerâs 25th-year catalogue, Colón characterizes the artist programs, âEvery project organized, seemed to capture the essence of Puerto Rican life in the Barrio. As in many of their productions, Tallerâs projects featured young artists freely expressing their views, political and otherwise. Photo exhibits, often orchestrated by Bonnie and Tom, were common because they dramatized the communityâs existence and serve as historical documentation of the Puerto Rican experience in the United States.â[11]

With projects such as these and the two-year oral history project âBatiendo La Olla,â completed in 1979, Taller cemented its role in the community.

|

| Danny Torres’s mural, Beinvenido a ” Centro de Oro,” Lehigh & N. 5th Street. |

In its new exhibition cycle, Claiming Places: Unity, Ownership, and âHogarâ (Home), Taller, now almost a 40-year-old institution with an eye to expand to a new and larger place, asks us to take note of our presence, to weigh what binds us to where we are, to think of what makes us who we are, and to imagine what we want our community to be. We are invited to take into account the impressions we leave and of our role as place-makers as we each shape our future. Students from Tallerâs education programs will show work dealing with the theme of place-making. There will be exhibitions in our galleries by César Viveros Herrera, Leticia Roa Nixon, Merián Soto, Esperanza Cortés, Dino Vázquez, and Tony Rocco and his students from Photography Without Borders as well a long a long-term creative and urban practice project going under the name of CP Lab with Ariel Vazquez and the Counter Narrative Society. We have set up a personalized blog to capture the elements of the shows and to allow comments from the public. The blog will, in the end, be an archive and a voice of this exploration. In January and May 2013, we will have two panel discussions bringing artists from the show together with scholars to discuss the issues raised in this cycle. Some of the people in the panel will be Lorrin Thomas, history professor at Rutgers University, Luis Aponte-Parés, community studies professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston, Johnny Irizarry, former director of Taller and director of La Casa Latina at the University of Pennsylvania, architect JC Calderon panel moderator, and Antonio Fiol Silva, principal architect on the team designing Tallerâs new building.

|

| A bilingual elementary school named after the famed Puerto Rican poet and  activist,  Julia de Burgos. |

Communities are transforming their spaces into personal places by integrating their experiences and reflecting their needs and hopes through the arts and cultural distinctions. Leaders in these communities further convey the needs and aspirations of the citizens in the collaborative organizations they create, like Taller, Juntos, Casa de Venezuela, Casa Monarca and Acción Colombia. âClaiming placeâ is a conscious act to be seen and heard to belong. Yet, the conversation is never static – circumstances change, wars happen, cataclysms occur, industries go, unemployment rises, and communities age, move, and sometimes mysteriously disappear. These are the challenges we face, as people and as a community, whether consciously or not. Through our exhibition cycle, Claiming Places: Unity, Ownership, and âHogarâ (Home), Taller, on its blog and in its programs and exhibitions, is providing a space for dialogue in the community. This is just the beginning of our journey in this yearlong conversation to explore a shared history in place making.

So please post your comments and subscribe to the Claiming Places blog.

Rafael Dasmast,

Visual Arts Program Manager

Dec. 8, 2012