Impermanence (On the Work of José Luis Cortés)

David Acosta

2015

…Éramos todo eso y mucho más: el eco de un espíritu sincero que cambió brisa por humo, fuego de sol por ceniza, gente de carne y hueso por máscaras anónimas, hombres de la ciudad que en el amor volvieron a sus islas infinitas. (We were that and much more The echo of a sincere spirit that traded the breeze. For smoke, the fire of the sun for ash, people of flesh and bone for anonymous masks, men of the city who in loving returned to their infinite islands.)

Manuel Ramos Otero, Invitacion Al Polvo

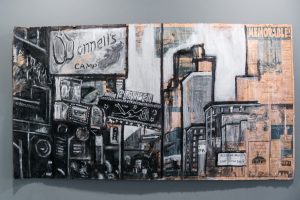

These are sacred spaces, richly immortalized in homosexual literature. Spaces which have become even more important in the romantic and idealized memories of men who  came of age before the AIDS epidemic. A landscape forever changed but intertwined erotically and historically with the locus of memory, desire and belonging. They are cultural spaces mined for meaning within the context of shifting perspectives and inevitable historical transitions, helped along as much by time as by the vicissitudes of an epidemic, and the ever changing and inevitable political, social and economic realities of a new century and the concentric circles of generations of gay communities who also move in and out of them, and shift.Old Sex District NYC 1997, Photograph of Time Square, NY

came of age before the AIDS epidemic. A landscape forever changed but intertwined erotically and historically with the locus of memory, desire and belonging. They are cultural spaces mined for meaning within the context of shifting perspectives and inevitable historical transitions, helped along as much by time as by the vicissitudes of an epidemic, and the ever changing and inevitable political, social and economic realities of a new century and the concentric circles of generations of gay communities who also move in and out of them, and shift.Old Sex District NYC 1997, Photograph of Time Square, NY

An example of this can be found in Cortés’s paintings and photographs documenting Times Square (before it became Disney) and the NYC of the 1990’s. This work is personally resonant for me as they are places that exist in my formative memory as a gay man. Cortés would document the surrounding buildings and neighborhood through photographs he took during breaks from his erotic dancing at the old Eros (an all gay adult theater and male go-go bar where he worked). One such photograph Old Sex District NYC 1997, captures it perfectly, it records an image easily recognizable in the work of John Rechy’s City of Night:

“Later I would think of America as one vast City of Night stretching gaudily from Times Square to Hollywood Boulevard — jukebox-winking, rock-n-roll moaning: America at night fusing its darkcities into the unmistakable shape of loneliness.”

The photograph is important in other ways as well, it is evocative of other paintings of buildings that would follow it. This photograph becomes the study he uses in his paintings Eros 1 and Eros 2. In the photographs and paintings from this period, Cortés seems aware of the ephemerality of the changing landscape. In capturing the images of that Times Square, Cortés was honoring the transitionality of the city, the inevitable disappearance of things, how cities change, how neighborhoods change, and how he himself would change. Paradise, a latter painting of an abandoned movie theater in Rio Piedras (also known for showing porn) creates continuity between NYC and Puerto Rico, two very different places (but for the theater), a theater in any place America, where many of us met the strangers of night and had some of our first sexual encounters. These spaces became part of the mythology of how we would remember and in latter years reconstruct sexual desire. Today, many of these buildings, parks, and streets, housed in gay ghettos across America have disappeared and or are fast disappearing (and with them many say, gay culture as we knew it,) not just the sex theaters or the cruising areas and porn book stores) but literary bookstores, boutiques, coffee shops, and bars.

The photograph is important in other ways as well, it is evocative of other paintings of buildings that would follow it. This photograph becomes the study he uses in his paintings Eros 1 and Eros 2. In the photographs and paintings from this period, Cortés seems aware of the ephemerality of the changing landscape. In capturing the images of that Times Square, Cortés was honoring the transitionality of the city, the inevitable disappearance of things, how cities change, how neighborhoods change, and how he himself would change. Paradise, a latter painting of an abandoned movie theater in Rio Piedras (also known for showing porn) creates continuity between NYC and Puerto Rico, two very different places (but for the theater), a theater in any place America, where many of us met the strangers of night and had some of our first sexual encounters. These spaces became part of the mythology of how we would remember and in latter years reconstruct sexual desire. Today, many of these buildings, parks, and streets, housed in gay ghettos across America have disappeared and or are fast disappearing (and with them many say, gay culture as we knew it,) not just the sex theaters or the cruising areas and porn book stores) but literary bookstores, boutiques, coffee shops, and bars.

Cortés’ interest in buildings and houses also attests to his deep interest in architecture, especially that of cities. In his renderings of these, (many of them in Puerto Ricowhere he currently lives) the palette is mostly black and white and the inevitable gray that comes from using both. Color is retained however, in the sky, the clouds or the vegetation, or in the people one can see through them. These buildings convey their sense of self-awareness, some seem abandoned as in Little Town Big Vistas, (2006) others are clearly inhabited, they are alive, as in For Those Who Tired of Glory and Richess, (2006) or Casas De Cemento also from 2006. People or objects or parts of the body inhabit these houses and buildings; torsos, eyes, legs, (as in Train Station Berlin 2003). These renderings transform the buildings from mere objects in a painting, to that of living things and the color he uses when breaking away from the black and white is important in depicting the life and movement within them.

Cortés’s series of paintings titled “Sex Ads” are another dimension of self-reference in his work. The series makes use of text: (both purposely written into the work, while also using the text which is already part of the printed page). The Sex Ad Series are a series of paintings where men advertise their services including their sexual preferences, their ethnicity, their size, and their price. The paintings reference the commercial side of desire, that which can be bought or sold for a price. Size matters in these ads, as does the fetishizing of race and the sexual currency of the top versus the bottom. Works such as Latin Beercan, or in Christie’s (2010); using the page of the NYT where the famous auction house is advertising the sale of art work by Mark Rothko, which Jose transforms into a sex ad for Andy, (appropriating and repurposing not only the ad but Rothko’s work), while making a statement on the commercialization of art and sex.

The Sex Series ads are evocative as well of a specific period when such ads were commonplace in most gay newspapers and could be found in some of the earliest gay publications such as One Magazine. These ads were in many ways the mainstay of these papers and in today’s social media world, these ads have moved onto electronic format, shrinking the market and forcing many of these publications to cease publishing, so in a sense these too are fast disappearing (and with advertising revenue shrinking daily,) many gay publications like the gay neighborhoods are vanishing.

In Jose Luis Cortés’s work there is honesty to the biographical references he chooses to convey. He is after all telling us his story, the story of his family, his Puerto Rico, his neighborhoods, and of his father’s memory. A memory that lives on in the newspapers that he continues to use as the canvass for his work. This is not new to art or artists as there is always in art, a biographical reference. It is however in his celebration of sex and desire, in his telling us what turns him on sexually, what he finds erotic that makes his work as an out Latino gay artist, and a Puerto Rican one significant. In the name for the current show En Blanco Y Negro, Jose Luis Cortés is aware that he moves from the margins to the center and back out again like the men and the cities of night so celebrated in the literary traditions that connect his work to an erotic past. A past he believes is worth celebrating and remembering.

If, at a given moment, everyone would say With one word what he is thinking, the six letters of DESIRE would form an enormous luminous scar, a constellation more ancient, more dazzling than any other, and that constellation would be like a burning sex in the deep body of night,….

From L. A. Nocturne: The Angels, Xavier Villaurrutia, translated by Elliot Weinberger & Esther Allen.

This exhibition and cycle was made possible by grants from PECO and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.